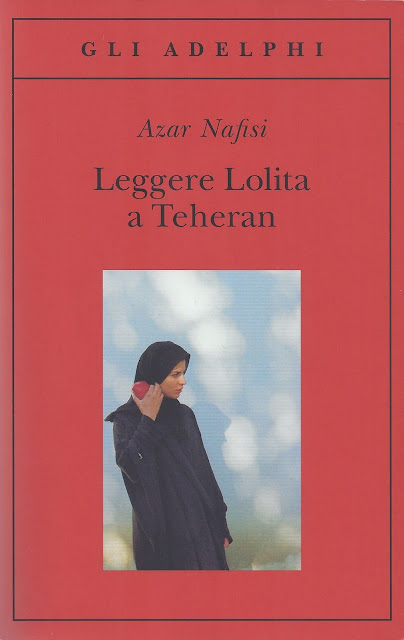

- Titolo: Leggere Lolita a Teheran

- Traduzione: Roberto Serrai

- Edizione: tredicesima, 2013

- Formato: cartaceo

- Casa editrice: Adelphi

- Collana: Gli Adelphi

- Pagine: 379

- Prezzo di copertina: € 12,00

- Refusi individuati: 3 + tagli

|

| "non riesco più e decifrare" (a decifrare) |

|

| "tre corsi di primo anni" |

|

Qui si sta parlando di Sanaz, Yassi non c'entra

(aveva scelto Sanaz guardando una foto di famiglia)

|

TAGLI

Il libro mi è piaciuto così tanto che ho deciso di leggerlo pure in originale, e qui ho avuto l'amara sorpresa.

La traduzione presentata da Adelphi è costellata di piccoli e grandi tagli. Diverse frasi, a volte intere pagine non sono state riportate. È come se qualcuno si fosse preso la briga di effettuare un editing ingiustificato del testo.

Per questioni di tempo e copyright non posso riportare tutti i passi incriminati, ma illustrerò diversi esempi, presi dalle ultime parti del libro.

In corsivo (nel testo originale) ho segnalato tutte le parti omesse.

Spero sempre nella buona fede delle persone, e spero che Adelphi possa spiegarmi il perché di questi tagli (ma è triste constatare che si è arrivati già alla quattordicesima edizione di un titolo così importante senza che nessuno ne abbia mai fatto menzione).

Testo originale (Parte III, cap. XXIX):

then the ruins of a house or two, where only the barest structure could be discerned in the rubble. Going to visit a friend or a shop or supermarket, we drove past these sights as if moving along a symmetrical curve. We would begin our ride on the rising side of the curve of devastation until we reach the ruined peak, followed by a gradual return to familiar sites and, finally, our intended destination.

Traduzione italiana (Parte III, cap. XXIX, pag. 266):

qualche altra danneggiata in modo più serio, e più in là una distesa di ruderi dove erano rimasti in piedi solo i muri portanti. (Il capitolo si conclude qui)

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte III, cap. XXXII):

Most of us were too tired even to respond.

In the next-to-last row on the window side, where Mr. Ghomi and Mr. Nahvi would sit, I find a quiet young man, an elementary school teacher. Let us call him Mr. Dori and move on. My glance hovers over Mr. Forsati, and Hamid, and then moves to the other side of the room, the girls’ side, past Mahshid, Nassrin and Sanaz. In the middle row, the seat on the aisle is occupied by Manna. I pause for a moment on Manna’s laughing face and then glance sideways towards the aisle—it is Nima that I seek.As I shift from Manna to Nima and back, I remember the first time I saw them in my class. Their eyes were shining in unison, reminding me of my two children whenever they entered a conspiracy to make me happy. By now, more than a few interested outsiders audited my classes. They were former students who continued to come to classes long after they had graduated, students from other universities, young writers and strangers who simply drifted in. They had little access to discussions about English literature and were prepared to spend extra time for no academic credit to attend these classes. My only condition was that they should respect the rights of the regular students and refrain from discussion during class hours. When one morning I found Manna and Nima standing by my office door, both smiling and eager to audit my seminar on the novel, I agreed without much hesitation.Gradually, the real protagonists in class came to be not my regular students, although I had no serious complaints against them, but these others, the outsiders, who came because of their commitment to the books we read.Nima wanted me to be his dissertation adviser, because no one in the faculty at the University of Tehran knew Henry James. I had promised myself never to set foot again at the University of Tehran, a place filled with bitter and painful memories. Nima coaxed me in many different ways, and in the end he convinced me. After class, the three of us usually walked out together. Manna was the quiet one and Nima would weave me stories about the absurdities of our everyday life in the Islamic Republic.Usually, he would walk beside me, and Manna would trail at a slightly slower pace by his side. He was tall and boyishly good-looking; not overweight but bulky, as if he had not yet lost his baby fat. His eyes were both kind and naughty. He had a surprisingly soft voice; not feminine, but soft and low, as if he could not raise it above a certain level.It had become a habit with us, a permanent aspect of our relationship, to exchange stories. I told them that listening to their stories, and through living some of my own, I had a feeling that we were living a series of fairy tales in which all the good fairies had gone on strike, leaving us stranded in the middle of a forest not far from the wicked witch’s candy house. Sometimes we told these stories to one another to convince ourselves that they had really happened. Because only then did they become true.In his lecture on Madame Bovary Nabokov claimed that all great novels were great fairy tales. So, Nima asked, do you mean to say that both our lives and our imaginative lives are fairy tales? I smiled. Indeed, it seemed to me that at times our lives were more fictional than fiction itself.

Traduzione italiana (Parte III, cap. XXXII, pag. 271):

Ma eravamo tutti talmente stufi di quei discorsi che non rispondevamo nemmeno. (Il capitolo si conclude qui)

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XI):

Under the chador, one could not see how curvy and sexy her figure really was. I had to control myself and not command her to drop her hands, to stop covering her breasts. Now that she was unrobed, I noticed how the chador was an excuse to cover what she had tried to disown—mainly because she really and genuinely did not know what to do with it. She had an awkward way of walking, like a toddler taking its first steps, as if at any moment she would fall down. A few weeks later, she stayed after class and asked if she could make an appointment to see me. I told her to come to our house, but she had become very formal and asked if we could meet at a coffee shop that my students and I were in the habit of frequenting. Now that I look at those times, I see how many of their most private stories, their confidences, were told in public places: in my office, in coffee shops, in taxis and walking through the winding streets near my home.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XI, pag. 329):

Con il chador, era impossibile accorgersi di quanto fosse provocante la sua figura. Dovetti farmi forza per non dirle che doveva smetterla di coprirsi il seno.

Alcune settimane dopo si trattenne oltre la fine dell'incontro e mi domandò se potevamo prendere un appuntamento nel solito caffè, quello in cui andavo con le studentesse.

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XI):

She lived in so many parallel worlds: the so-called real world of her family, work and society; the secret world of our class and her young man; and the world she had created out of her lies. I wasn’t sure what she expected of me. Should I take on the role of a mother and tell her about the facts of life? Should I show more curiosity, ask for more details about him and their relationship? I waited, trying with some effort to pull my eyes off the hypnotic red carnation and to focus on Nassrin."I wouldn’t blame you if you made fun of me," she said with great misery, twirling her spoon in the puddle of ice cream.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XI, pag. 330):

Viveva ormai in diversi mondi paralleli: il cosiddetto mondo reale, quello della famiglia, del lavoro e della società; il mondo segreto dei nostri incontri e del suo ragazzo; infine, il mondo che aveva creato con le sue bugie. Non sapevo bene che cosa si aspettasse da me.

"Se mi trova ridicola la capisco".

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XVI):

If you promise you’ll behave, my magician said on the phone, I have a nice surprise for you. We arranged to meet at a popular coffee shop that opened into a restaurant and had its own pastry shop in the front. The name eludes me, although I am sure, like so many other places, it must have been changed after the revolution.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XVI, pag. 345):

"Se prometti di comportarti bene", mi disse il mio mago al telefono "ho una bella sorpresa per te". Ci demmo appuntamento in un famoso caffè di cui adesso mi sfugge il nome. Ma tanto non importa, lo avranno cambiato, li cambiano tutti.

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XVIII):

Our decision to leave Iran came about casually—at least that is how it appeared. Such decisions, no matter how momentous, are seldom well planned. Like bad marriages, they are the result of years of resentment and anger suddenly exploding into suicidal resolutions. The idea of departure, like the possibility of divorce, lurked somewhere in our minds, shadowy and sinister, ready to surface at the slightest provocation.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XVIII, pag. 350):

La decisione di lasciare l'Iran arrivò per caso - o almeno così parve. Svolte del genere, per quanto importanti, non sono quasi mai pianificate con precisione. L'idea della partenza covava nascosta in qualche angolo buio della mente, ostile e sinistra, pronta a uscire allo scoperto alla minima provocazione.

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XVIII):

Your place will be so empty, Yassi had said, using a Persian expression—but they too began to nurture their own plans to leave.

As soon as our decision was final, everyone stopped talking about it. My father’s eyes became more withdrawn, as if he were looking at a point beyond which we had already vanished into the horizon. My mother was suddenly angry and resentful, implying that my decision had once more proven her worst suspicions about my loyalty. My best friend energetically took me shopping for presents and talked about everything but my journey, and my girls barely registered the change; only my children mentioned our impending departure with a mixture of excitement and sadness.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XVIII, pag. 351):

"Il suo posto sarà così vuoto" aveva detto Yassi, ricorrendo a un'espressione tradizionale persiana.

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XIX):

My magician was not my “patient stone,” although he never told his own story—he claimed people were not interested in that. Yet he spent sleepless nights listening to and absorbing others’ troubles and woes, and to me his advice was that I should leave: leave and write my own story and teach my own class.

Perhaps he saw what was happening to me more clearly than I did. What I now realize is that, ironically, the more attached I became to my class and to my students, the more detached I became from Iran. The more I discovered the lyrical quality of our lives, the more my own life became a web of fiction. All of this I can now formulate and talk about with some degree of clarity, but it was not at all clear then. It was much more complicated.

As I trace the route to his apartment, the twists and turns, and pass once more the old tree opposite his house, I am struck by a sudden thought: memories have ways of becoming independent of the reality they evoke. They can soften us against those we were deeply hurt by or they can make us resent those we once accepted and loved unconditionally.

We sit again with Reza around the same round dining table, under the painting of green trees, talking and eating lunch, the forbidden ham-and-cheese sandwiches. Our magician does not drink. He refuses to compromise with the counterfeits: the bootleg videos and wine, censored novels and films. He does not watch television, nor does he go to the movies. To watch a beloved film on video is anathema to him, although he obtains tapes of his favorite movies for us. Today he has brought us homemade wine, its color a sinful pale pink, poured into five vinegar bottles. Later, I take the wine home and drink it. Something has gone wrong and the wine tastes like vinegar, though I do not tell him.Perhaps he saw what was happening to me more clearly than I did. What I now realize is that, ironically, the more attached I became to my class and to my students, the more detached I became from Iran. The more I discovered the lyrical quality of our lives, the more my own life became a web of fiction. All of this I can now formulate and talk about with some degree of clarity, but it was not at all clear then. It was much more complicated.As I trace the route to his apartment, the twists and turns, and pass once more the old tree opposite his house, I am struck by a sudden thought: memories have ways of becoming independent of the reality they evoke. They can soften us against those we were deeply hurt by or they can make us resent those we once accepted and loved unconditionally.We sit again with Reza around the same round dining table, under the painting of green trees, talking and eating lunch, the forbidden ham-and-cheese sandwiches. Our magician does not drink. He refuses to compromise with the counterfeits: the bootleg videos and wine, censored novels and films. He does not watch television, nor does he go to the movies. To watch a beloved film on video is anathema to him, although he obtains tapes of his favorite movies for us. Today he has brought us homemade wine, its color a sinful pale pink, poured into five vinegar bottles. Later, I take the wine home and drink it. Something has gone wrong and the wine tastes like vinegar, though I do not tell him. The hot subject of the day was Mohammad Khatami and his recent candidacy.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XIX, pag. 352):

Il mago non era la mia "pietra paziente", ma certo passava notti intere ad ascoltare gli altri.

In quei giorni si parlava incessantemente di Mohammad Khatami e della sua recente candidatura.

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XX):

I was on the phone when Nassrin arrived. Negar, who had opened the door, kept shouting, quite unnecessarily, Mom, Mom, Nassrin is here! A few minutes later a shy Nassrin entered, standing by the door as if already regretting her visit. I gestured for her to wait for me in the living room. I’ll have to call you later, I told my friend. One of my girls is here to see me. Girls? she said—she knew very well what I meant. Students, I said. Students! Get a life, woman. Why don’t you return to teaching? But I am teaching. You know what I mean. By the way, talking of your students, your Azin is going to drive me crazy. That girl doesn’t know her own mind—either that or she’s playing a game I don’t understand. She’s worried about her daughter, I said hurriedly. But listen, I really have to go. I’ll call you later.When I entered the living room, Nassrin was staring at the birds-of-paradise and chewing her nails with the distracted focus of a professional nail chewer. I should have guessed before that she belonged to the category of people who bite their nails, I remember thinking—she must have exercised a great deal of restraint in class.At the sound of my voice, she turned around abruptly and impulsively hid her hands behind her back. To cover the awkwardness she had brought into the room, I asked her what she wanted to drink. Nothing, thank you. She had not taken her robe off, only unbuttoned it, revealing the outlines of a white shirt tucked into a pair of black corduroys. She was wearing Reeboks and her hair was pulled back into a ponytail. She looked like a pretty girl, young and fragile, like any other girl from any other part of the world. She shifted restlessly from one leg to another, reminding me of the first time I had seen her, almost sixteen years earlier. Nassrin, stand still for a moment, I said quietly. Better yet, sit. Sit down, please—no, let’s go downstairs to my office; it’s more private.I was trying to delay what she had come to tell me.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XX, pag. 354):

Quando arrivò Nassrin ero al telefono. Negar, che aveva aperto la porta, continuava a urlare, senza che ce ne fosse bisogno: "Mamma, mamma, c'è Nassrin!". Pochi istanti dopo Nassrin si fermò titubante sulla soglia, come se si fosse già pentita di quella visita.

In soggiorno, Nassrin guardava fuori, e si mangiava le unghie con la concentrazione distratta di una professionista. Non si era tolta la veste, l'aveva solo sbottonata, lasciando intravedere una camicetta bianca infilata in un paio di pantaloni di velluto neri, e le Reebok. Portava i capelli a coda di cavallo. Sembrava una qualsiasi ragazza carina di un paese qualsiasi.

Mi accorsi che cercavo di rimandare il discorso che era venuta a farmi.

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XX):

We had reached my office. She waited for me to open the door, shifting her weight from one leg to another, as if neither leg would take responsibility for its burden. I could tell by her pale color and the stunned expression on her face that I had asked the wrong question. I’m done with him, she muttered as we entered the room.

How are you leaving? I asked her once we had sat down, she with her back to the window and I slumped on the couch against the wall with its large painting—much too large for the small room—of the Tehran mountains. Smugglers, she said. They still won’t issue me a passport. I’ll have to make my way to Turkey by land and wait for my brother-in-law to pick me up.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XX, pag. 354):

Eravamo arrivate nel mio studio. Mi aspettò, prima di aprire la porta. Dal colorito pallido e dall'espressione attonita del suo volto capii che forse avevo fatto la domanda sbagliata. "Con lui è finita" disse piano mentre entravamo nella stanza.

"Come te ne andrai?" le chiesi una volta che ci fummo sedute. "Coi frontalieri" disse. "Il passaporto non me lo danno. Dovrò trovare il modo di arrivare in Turchia via terra e aspettare che mio cognato mi venga a prendere".

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XXI):

(Nima would call later that night. “Manna is afraid you don’t like her anymore,” he said half jokingly. “She asked me to call.”)

Other people’s sorrows and joys have a way of reminding us of our own; we partly empathize with them because we ask ourselves: What about me? What does that say about my life, my pains, my anguish? For us, Nassrin’s departure entailed a genuine concern for her, and anxieties and hopes for her new life.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XXI, pag. 359):

(Nima quella sera mi telefonò. "Manna ha paura che lei non le voglia più bene" disse in tono semiserio. "Mi ha chiesto di chiamarla").

La partenza di Nasrin suscitava in noi una sincera preoccupazione per lei, e ansie e speranze per la sua nuova vita.

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XXI):

She described the feel of the wind and the sun on her hair and her skin—it was always the same sensation that was so startling. It had been the same with me and would be so later with Yassi and Manna.

In the Damascus airport she had been humiliated by what she was assumed to be, and when she returned home, she felt angry because of what she could have been. She was angry for the years she had missed, for her lost portion of the sun and wind, for the walks she had not taken with Hamid.In the Damascus airport she had been humiliated by what she was assumed to be, and when she returned home, she felt angry because of what she could have been. She was angry for the years she had missed, for her lost portion of the sun and wind, for the walks she had not taken with Hamid. The thing about it, she had said with wonder, was that walking with him like that had suddenly transformed him into a stranger. This was a new context for their relationship; she had become a stranger even to herself. Was this the same Mitra, she asked herself, this woman in jeans and a tangerine T-shirt walking in the sun with a good-looking young man by her side? Who was this woman, and could she learn to incorporate her into her life if she were to live in Canada?

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XXI, pag. 360):

Ci descrisse la sensazione del vento e del sole tra i capelli e sulla pelle, che ogni volta ci sorprendeva. Il problema, aveva aggiunto con stupore, era che camminare con lui a quel modo lo aveva trasformato di colpo in un estraneo. Ma lei stessa non si era riconosciuta più: è la Mitra di sempre, si domandava, questa donna con i jeans e la maglietta color mandarino che se ne va sotto il sole con un bel ragazzo a fianco? E quella strana donna, un giorno, sarebbe andata con lei fino in Canada?

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XXII):

We spent long hours talking about our feelings, our ideas of home—for me portable, for him more traditional and rooted.

I told him in detail about the arguments we had had in class that day. After they left, I couldn’t get rid of this idea of sexual molestation. I said, I keep tormenting myself with the thought that that’s how Manna must feel.Bijan didn’t respond—he seemed to be waiting for me to elaborate—but suddenly I had nothing more to say. Feeling a little lighter, I stretched and picked at a few pistachio nuts. Have you ever noticed, I said, cracking a nut, how strange it is when you look in that mirror on the opposite wall that instead of seeing yourself, you see the trees and the mountains, as if you have magically willed yourself away?

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XXII, pag. 363):

Passavamo ore a parlare dei nostri sentimenti, della nostra idea di "casa" - per me era qualcosa di portatile, lui era su posizioni più tradizionali, tipo mettere radici e via dicendo.

"Hai mai notato" gli domandai aprendo un pistacchio "com'è strano quando guardi in quello specchio e invece di vedere la tua immagine riflessa ci trovi gli alberi e le montagne, quasi fossi riuscito magicamente, con la forza del pensiero, a farti sparire?".

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XXIII):

It was a warm summer day, about a fortnight after my conversation with Bijan. I had taken refuge in a coffee shop. It was really a pastry shop, one of the very few that still remained from my childhood. It had great piroshki for which people stood in long lines, and near the entrance, next to the large French windows, two or three small tables. I was sitting at one of these with a café glacé in front of me. I took out my pen and paper and, staring into the air, started to write. This staring into the air and writing had become my forte, especially in those last few months in Tehran.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XXIII, pag. 364):

Era una tiepida giornata d'estate, circa quindici giorni dopo quella conversazione con Bihan. Mi ero rifugiata in un caffè dove andavo da bambina. Facevano certi piroški favolosi per i quali la gente faceva la fila, e fuori, accanto alle grandi portefinestre c'erano due o tre tavolini. Ero seduta proprio a uno di quelli, con un café glacé davanti. Tirai fuori carta e penna e, dopo aver guardato un po' per aria, cominciai a scrivere.

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XXIII):

Do you remember our discussions of Wuthering Heights?

Yes, I remembered them, and as we talked I remembered her more clearly too; images chased away her present unfamiliar face and replaced it with another, now also unfamiliar. I returned in my mind to that classroom, on the fourth floor, to the third—or was it the fourth?—row near the aisle. I can just about pick out two faces, almost identical in their bland disapproval, taking notes. They were there when I entered the class and would linger after I left. Most of the others looked on them with suspicion. They were quite active in the Muslim Students’ Association and did not mix well even with the more liberal elements in the Islamic Jihad, like Mr. Forsati.I remember her. I remember that particular discussion of Wuthering Heights, because I remember how Miss Ruhi had unglued herself from her friend and followed me out of the classroom...

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XXIII, pag. 365):

"Ricorda le nostre discussioni su Cime Tempestose?".

Sì, me le ricordavo bene, perché la signorina Ruhi mi aveva seguita fuori dall'aula...

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XXIII):

She said something about other professors, their delicacy in censoring even the word wine out of the stories they taught, lest it offend the Islamic sensibilities of their students. Yes, I thought, and they have been stuck teaching The Pearl. I told her she could drop the class or take the matter to higher authorities

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XXIII, pag. 365):

Lei accennò ad altri professori, alla loro delicatezza nell'espungere addirittura la parola vino dai testi, per non offendere la sensibilità degli studenti. Le dissi che poteva abbandonare il corso oppure denunciarmi alle autorità

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XXIII):

I asked her how old her daughter was. She said, Eleven months, and, after a pause, with a playful shadow of a smile: I named her after you. After me? I mean, she has a different name on her birth certificate—she is called Fahimeh, after a favorite aunt who died young—but I have a secret name for her. I call her Daisy. She said she had hesitated between Daisy and Lizzy. She had finally settled on Daisy. Lizzy was the one she had dreamed of, but marrying Mr. Darcy was too much wishful thinking. Why Daisy? Don’t you remember Daisy Miller? Haven’t you heard that if you give your child a name with a meaning she will become like her namesake? I want my daughter to be what I never was—like Daisy. You know, courageous.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XXIII, pag. 366):

Le domandai quanti anni aveva sua figlia. "Undici mesi" rispose, e poi aggiunse, con un accenno di sorriso: "Ho scelto il nome pensando a lei". "A me?". "Sì. Voglio dire, sul certificato di nascita il nome è diverso - c'è scritto Fahimeh, come la mia zia preferita che è morta molto giovane -, ma io la chiamo Daisy". "E perché Daisy? Non te la ricordi Daisy Miller? Non la sopportavi". "No, però si dice che se si battezza un figlio pensando a qualcuno in particolare, il bambino diventerà come la persona che porta quel nome. E io voglio che mia figlia sia come io non sono mai stata - e cioè come Daisy. Sa, insomma, coraggiosa".

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XXIV):

He’s not a beau, Sanaz objected, giggling now, clearly enjoying herself after a long period of depression. He’s a friend of Ali’s. He’s here on a visit from England, she informed me, feeling that an explanation was in order. We knew each other before—we were sort of friends, she said, through Ali. He was supposed to be our best man, you see. So he came to pay me a visit, just to be nice.

Mitra’s dimples and Azin’s knowing smile suggested that there was more to “nice” than met the eye. What? said Sanaz. He’s not good-looking. Actually, she said, narrowing her eyes, he’s sort of ugly. Perhaps more like rugged? suggested Yassi hopefully. No, no, more like, well, more like ugly, but a very nice man, considerate and kind. My brother keeps making fun of him, she said, and you know sometimes I feel like going with him or something. The other day, he was saying how he can’t wear short sleeves or go swimming over here. After he left, my brother kept mimicking him and saying, Very clever new method of seduction and my silly sister is just the kind of girl to fall for it.The waiter came in to take my order.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XXIV, pag. 369):

"Non è il mio fidanzato" ribatté Sanaz, ridacchiando. "È un amico di Ali. È qui in visita dall'Inghilterra" mi informò, sentendo che era opportuna una spiegazione. "Ci conoscevamo già - eravamo più o meno amici," precisò "per via di Ali. Doveva far da testimone, sa? Ora è venuto a trovarmi, ma solo per gentilezza". Ma le fossette di Mitra e l'eloquente sorriso di Azin suggerivano invece che c'era dell'altro. "Che avete?" domandò Sanaz.

Il cameriere entrò a prendere la mia ordinazione.

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XXIV):

and I am holding on to my frosted glass protectively, as if it might be snatched from me at any moment.

Later, I showed the pictures we’d taken in those last few weeks to my magician. You get a strange feeling when you’re about to leave a place, I told him, like you’ll not only miss the people you love but you’ll miss the person you are now at this time and this place, because you’ll never be this way ever again.The waiter brought us our coffee in small different-colored cups, and while drinking, we pondered the trials and tribulations of being a writer in Iran

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XXIV, pag. 369-370):

e io stringo il mio bicchiere ghiacciato come per proteggerlo, come se potessero portarmelo via da un momento all'altro.

Il cameriere ci servì il caffè alla turca, e mentre lo bevevamo riflettemmo sulla difficoltà di essere uno scrittore in Iran

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XXV):

Before he talks, let me have him go to the kitchen, because he is a very hospitable person and would definitely not leave me talking for so long without some offer of tea or coffee, or perchance some ice cream? Today, let it be tea, in two mismatched mugs, his brown, mine green. His graceful, aristocratic poverty, his mugs, his faded jeans, his T-shirts, his chocolates. While he is in the kitchen, let me be silent and consider how meticulously he has created his rituals—reading the paper at a certain hour after breakfast, the morning and evening walks, the answering of the phone after two rings. I am overtaken by a sudden tenderness: how tough he seems to us, yet how fragile is his life.As he carries in the two mugs of tea, I tell him, You know, I feel all my life has been a series of departures. He raises his eyebrows, placing the mugs on the table, and looks at me as if he had expected a prince and all he could see was a frog.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XXV, pag. 370-371):

Prima che parli lo faccio andare in cucina, e poi, mentre porta le tazze di tè, gli dico: "Sai, mi sento come se tutta la mia vita fosse stata un'unica serie di partenze". Mi guarda come uno che si aspettava una principessa e invece si è trovato di fronte una ranocchia.

----------------------------

Testo originale (Parte IV, cap. XXVI):

We speak of facts, yet facts exist only partially to us if they are not repeated and re-created through emotions, thoughts and feelings. To me it seemed as if we had not really existed, or only half existed, because we could not imaginatively realize ourselves and communicate to the world, because we had used works of imagination to serve as handmaidens to some political ploy.

Traduzione italiana (Parte IV, cap. XXVI, pag. 372):

"I fatti concreti di cui parliamo non esistono, se non vengono ricreati e ripetuti attraverso le emozioni, i pensieri e le sensazioni"